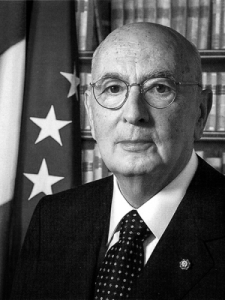

Lecture by the President of the Italian Republic

Giorgio Napolitano

to the International Institute for Strategic Studies

London, 19 May 2009

Will Europe live up to its responsibilities in a globalized world?

Dear Prof. Howard, first of all let me thank you for your kind introduction, and allow me to thank the IISS for your invitation to me, as President of the Republic of Italy, to join the by now long list of statesmen, starting with my friend Henry Kissinger, who have been asked to give an Alastair Buchan lecture.

Now, when thinking of a possible title for my lecture, Sir Michael, I realised that your impressive Memorial lecture of last year -- "Are we "at war"?" -- ended with a question mark. I then remembered that the title of my last lecture in Britain, held at the London School of Economics in October 2006, also ended with a question mark.

Its title was: "Is there a future for European integration?". This prompted me again to use a title ending with a question mark. After all, when thinking of the current state of the world, our minds fill with unanswered questions. So I came up with a title and a question which is uppermost in my mind today and may well be in yours: "Will Europe live up to its responsibilities in a globalized world?"

Then the words spoken long ago by the man who was arguably last century's most important European statesman, Winston Churchill, came back to me. I would like to recall them to those of you who are too young to remember them. Speaking at the Albert Hall on May 14, 1947 in one of the memorable speeches which helped lay the foundations of a united Europe after the horrors of the Second World War, he said : "We hope to reach again a Europe in which men will be proud to say : 'I am European', as once they were to say 'Civis Romanus sum'".

And I wonder : can we become as proud of being European as he dreamt we would?

Of course, we have succeeded in peacefully creating a democratic European Union which spans practically the whole of our Continent. But the political and economic scene on which we act has, at the same time, become much larger, to the point that it covers the entire world.

And ours is a world where the centre of gravity of international political and economic relations has shifted far away from Europe. Our continent's demographic and economic relative weight is undoubtedly shrinking. But should we draw the conclusion that Europe's role in the world is destined to become marginal? No, if we consider how important Europe's legacy is in terms of historical experience, of political and cultural creativity, of scientific research, of human capital and of social solidarity. That is what enables Europe to make today a decisive contribution to the process of rethinking and reshaping development and the international order, as the depth and complexity of the current crisis unquestionably requires we do.

Europe is not fated to become marginalized if we can "live up to our responsibilities in a globalized world". This is not the world that people variously imagined in the aftermath of the revolutions which swept across Central and Eastern Europe, and of the fundamental historical watershed that began with the fall of the Berlin Wall and even before with the collapse of the Communist regime in Poland. At that time some imagined a world in which the clash between conflicting ideologies would be followed by a "clash of civilizations". Some looked forward to the reign of a form of liberal democracy that now would lay unopposed, and with it to "the End of History". Others more simply imagined a world that would "go out of control" following the collapse, together with the fall of the Soviet empire, of the bipolar order which the two superpowers had maintained.

The globalized world that has arisen since, particularly in the last decade, coincides with none of those predictions, although it does in part mirror some of the tendencies, risks and doubts that were voiced.

Making real and steady progress towards a world community of peaceful and friendly democracies is no easy task. Nor is it easy for Europe to play a leading role in such a movement.

Ours are not simple choices, as we can see if we just consider some of the dilemmas which we have had to face in recent years and which await us in the future. Looking back to last year, I've realized that rarely in world history have 12 months been so full of fateful events and of so many difficult challenges, but also perhaps full of so many opportunities for all nations.

To begin with we are now experiencing what is probably the worst economic and financial crisis since 1929, a crisis affecting all continents and challenging all governments and international institutions - not to speak of the dangers of misguided protectionism, political instability and perhaps even conflicts.

Secondly, a war which could have had disastrous consequences for peace in our continent did indeed take place in Georgia. And beyond the responsibility for starting that crisis, the following invasion and occupation of Georgian territories by Russian armed forces was widely condemned. Efforts by the European Union, then under the vigorous leadership of French President Sarkozy, were immediate and effective, leading to the withdrawal of Russian forces from Georgia, if not from those regions which had claimed independence.

However, a serious crisis in political relations between the Russian Government and European as well as Atlantic institutions followed. People even spoke of "a new Cold War". Gradually this danger was avoided and relations with Moscow slowly became more friendly.

However, the Bush Administration's decision, with the support of Polish and Czech Governments, to set up missile defence bases in those two countries in order to counter growing Iranian nuclear potential, and rash threats by Russia to respond to such initiatives with dangerous military countermeasures, contributed to the emergence of new tensions in what were once known as "East-West relations".

But a third major event, which occurred in the last 12 months, was undoubtedly the United States' new political course. Today we are all well aware that the American Presidential elections and the forceful and imaginative foreign policy initiatives of the Obama Administration appear to have opened new prospects. President Obama's successful mission to Europe, and his meeting with President Medvedev, have led the two nuclear "Superpowers" (I think this definition is still correct) to agree to start negotiations on "a new strategic arms reduction treaty with Russia" (I am quoting from the American President's speech in Prague on April 5) aimed at "a new agreement by the end of this year that is legally binding".

On America's commitment to missile defence systems, President Obama said, as you surely remember, that "as long as the threat from Iran persists" America intends "to go forward with a missile defence system that is cost-effective and proven". At the same time, this will be accomplished, as Vice President Biden pointed out in his speech in Munich on February 7 in consultation with "you, NATO allies, and with Russia".

These new developments in Europe's and America's relations with Russia are welcome, and have been interpreted as the start of a new phase of strategic negotiations, and not just in the field of armaments ; although some tensions tend to reappear, and need to be kept under control.

I mentioned before that international developments have presented not only new challenges and threats, but also new opportunities which certainly concern the European Union as well.

However, and I quote again a passage from Sir Michael Howard's Memorial lecture, the events of September 11 and successive terrorist attacks in Europe and elsewhere, prove that "global society is vulnerable, with no lack of people ready to disrupt it, or ready to turn to terrorism. This threat accompanies the development of our global society like an inescapable shadow".

This situation has highlighted once again the problem and possibility of nuclear disarmament. As President Obama said in his Prague speech, since the end of the Cold War "the threat of global nuclear war has gone down, but the risk of nuclear attack has gone up". This assessment led him to proclaim "America's commitment to seek the peace and security of a world without nuclear weapons". A noble aim, indeed, although he immediately added: "this goal will not be reached quickly - perhaps not in my lifetime".

As a matter of fact, we are all aware that deterrence still plays a fundamental role in preventing nuclear wars. We are also aware that the spread of nuclear weapons, and the possibility that some may fall into the hands of terrorist organisations, reduces the effectiveness of deterrence based on Mutual Assured Destruction, and lends new importance and value to anti-missile defence. The balance between those somewhat conflicting aims will have to be carefully examined with the purpose of preventing nuclear proliferation and nuclear attacks hoping that all major powers will agree on the measures to be adopted.

What I have mentioned above are some of the most recent developments in the overall framework of the problems to be overcome in order to guarantee international security and stability as an essential part of effective world governance. There is no need to list all the challenges and threats that have emerged in the last decade, especially since September 11, in order to wonder what part Europe is destined to play. We must discuss the issue frankly and critically because we must live up to our responsibilities in various areas, and specifically and concretely in the field of security.

Europe - or more precisely the European Union - has done much in recent years to reach a definition of a new concept of security. It has in part done so through not always easy discussions with our fundamental partner, the United States. At this point we can say that there is substantial agreement in Europe and on both sides of the Atlantic on a broader, more inclusive and multidimensional concept of security. In fact, following the major contribution made by the European Union with its 2003 European Security Strategy, definitions that are by now entirely similar can be found in the most recent documents. Examples include the important joint declaration on security and defence policy agreed early in February by Chancellor Merkel and President Sarkozy, and the speech by the Secretary General of NATO in Paris a month later. After noting how the cleavage between the notion of defence and the notion of security is tending to disappear, the latter shifted to issues such as cyber-defence, energy security and climate change (while the Franco-German document also mentioned the question of migrations).

It is obvious therefore that such a concept of security implies flexible and open approaches to the present complex global context as well as to specific crisis areas. Such approaches may variously include resorting to military or civilian means, to political-diplomatic initiatives or to measures aimed at promoting economic and social development - the latter being vital, together with support to institution building in order to create the conditions needed for democracy to grow and for human rights to flourish.

I should, however, like to say clearly that broadening and enriching the concept of security, although necessary, is not a good reason for avoiding discussion of military matters and of a joint commitment in the field of defence. There is no avoiding it for the European Union.

In its relations with the United States Europe is still suspected of wanting to lay the responsibility for, and the burden of, its defence and security on the shoulders of its American ally. We must be absolutely sure that the European Union and/or its individual Member States does and do not effectively underestimate their joint responsibility for the safeguard of their individual security interests and of those of the Union as a whole.

Awareness of such responsibilities was clearly and eloquently expressed in Europe's participation with military as well as civilian means in peacekeeping and stabilization missions in crisis areas under the responsibility of the United Nations, NATO or the European Union itself. This is a new development, and I should like to stress its significance and relevance as part of the international community's response to the new threat posed by the rise of transnational terrorism. I need give no figures but will only mention the 8,500 Italian troops currently deployed in a number of missions, principally in the Balkans, Lebanon and Afghanistan.

But at the same time it cannot be denied that during the last decade it has been slow and uphill work to provide the European Union with the instruments it needs to play its part in safeguarding collective security. The von Wogau report presented to a plenary session of the European Parliament and approved last February made no attempt to conceal the serious grounds for dissatisfaction at the progress made between 2003 (when a European Security Strategy was adopted) and today in the field of European defence cooperation. The report attributes such lack of progress to the harsh finding that Member States "still too often view their own interests from a purely national perspective".

Such short-sightedness also helped weaken the important decision taken by the European Council in 2000 to set up a European Union Political and Security Committee and a Military Committee charged with broad responsibilities - responsibilities which, despite the problems they face, they continue to try to fulfil.

Another limitation on the Union's efforts in the field of defence and security is the question of available resources. This may cast some doubt on the likelihood of achieving all the goals eloquently and precisely set out in the Declaration on Strengthening EU Capabilities submitted to the Council in December 2008.

The point is that given the difficult situation faced by Member States' public finances - particularly with the current global financial and economic crisis - the way ahead lies in a significant increase in the productivity of European defence spending, still much lower than that of the United States defence budget and above all suffering from poor effectiveness and coordination. Rationalization is required, including an end to the costly and unproductive duplication of structures. Each EU Member State has its own national Defence organization. Expenditure in research and technology and procurement is not at all specialized, since for political reasons each Nation wants to maintain a complete defence structure, leading to a redundancy of basic military assets, a lack of force multipliers and, in general, a lack of high-grade capabilities.

Such are the contradictions and weakness that have to be overcome while also strengthening a crucial instrument like the European Defence Agency with the objective, among others, of helping develop a European defence industry.

From any point of view, all this effectively calls for abandoning the traditional formulation and national management of problems and public policies in favour of joint, European-level policies and structures.

That is the way to achieve an effective partnership between the European Union and NATO and also to fully exploit the opportunities provided under the so-called "Berlin-Plus arrangements" of 2003, which give the Union access "to NATO's collective assets and capabilities for EU-led operations".

Qualms concerning more rational and productive forms of integration in the phase currently experienced by the European Union can no longer be justified in the name of what were once "ideological" prejudices and suspicions about European unity. They should be abandoned, though not as a form of homage to opposed doctrines and theories but as a response to objective facts, to ineluctible changes in the world order and to new challenges to the growth and security of European society which individual Member States are manifestly unable to meet. Only through the Union and its institutions (which should be renewed and strengthened on the basis of the Treaty of Lisbon at least) can Europe "live up to its responsibilities".

I refer to the responsibilities inherent in the still- fundamental Euro-Atlantic partnership and first and foremost to the contribution to be given to implementing the orientations that emerged from the meeting of NATO Heads of State and Government held in Strasburg and Kehl and of its concluding "Declaration on Alliance Security". Specifically, that will involve contributing to drawing up a new Strategic Concept, "to better address today's threats and to anticipate tomorrow's risks", ten years after the Washington document "An alliance for the 21st century".

Such threats and risks certainly include not only those deriving from a state of widespread conflictuality, which transnational terrorism has been quick to exploit, but also from the concrete challenges presented by three key crisis areas: the Afghanistan-Pakistan region, the wider Middle East and the Horn of Africa (just consider Somalia as the base for a new form of dangerous piracy).

In particular, the picture offered by developments in Afghanistan is far from encouraging. This is the first area where the International Community is to make its main effort to counter the global threat posed by fanaticism and obscurantism. A failure in our efforts to stabilize Afghanistan and promote the development of its institutions and civil society would have very serious consequences, in the whole region.

I, therefore, firmly believe that a more active European participation in peace-keeping and peace-enforcement operations in Afghanistan, as forcefully suggested by the American Administration, should be seriously considered, in our own interest first of all, having in mind the threat of fundamentalist Islamic terrorism to Europe. I take very seriously President Obama's warning that Europe may be under greater threat from terrorism than the United States themselves. Afghanistan may appear to be very distant from us. But distances matter very little in today's world. It is a dangerous illusion to believe that Afghanistan future does not concern the future of peace in the world.

The same can be said of the crisis still open in the Middle East.

After continuing missile attacks from the Gaza Strip against Israeli cities, the ensuing war took a very high toll in lives and destruction. Serious differences persist among Palestinians between those in favour of continuing negotiations aimed at a two-state solution, which is undoubtedly the only viable option, and those who at least formally oppose them.

On the other hand my recent contacts with leaders in the Region leave some room for hope : negotiations between the two Palestinian sides continue and apparently show some progress.

On the Israeli side, elections resulted in the formation of a Government which so far does not appear to accept some of the partial agreements reached in the preceding Israeli-Palestinian negotiations. A more active European role on all issues involved in the peace process (economic as well as political and potentially military too) would certainly be viewed very favourably in the region, not only by the Palestinians.

More generally, Europe will have to demonstrate in the near future that it is capable of making a significant contribution to the developments which - as I mentioned before - are becoming possible in the system of international relations, thanks, among other things, to new initiatives on the part of the US Administration.

I mentioned already the desirable and necessary developments in relations with the Russian Federation and a renewed round of disarmament negotiations, particularly as regards nuclear weapons.

And when I say "Europe will have to demonstrate", I refer to the concrete reality of the European Union, with its existing "external" policies such as the policy towards Russia, or its Eastern Partnership or - in another direction - its Euro-Mediterranean Partnership. And I refer to a European Union which can increasingly assume its own profile and its own role in the overall development of international relations.

Europe must - let me just touch on this point - show itself capable of contributing significantly to the solutions to the underlying problems which the global economic and financial crisis which broke out last year posed and still poses. Such solutions are to be sought and identified in a vast framework of consultations which has recently grown in size up to the G-20. The latter is the forum for discussions with such new emerging powers as India and China and with the representatives of other realities, now to be reckoned, within various continents.

Reference is sometimes made, vaguely, to the need for a new Bretton Woods. But it must be said that the world has changed radically since the years of the complex preparatory work and final conclusion of the Bretton Woods Agreement.

The leading actors of that enterprise were substantially the United States and Great Britain, the latter represented by a great scholar, writer and public servant, John Maynard Keynes. A figure of extraordinary cultural and technical merit, Keynes nonetheless had to renounce some of his ideas and fundamental demands. But let me recall what he said at the Bretton Woods Conference, using words that showed the depth of his vision :

"...We have been operating, moreover, in a field of great intellectual and technical difficulty. We have had to perform at one and the same time the tasks appropriate to the economist, to the financier, to the politician, to the journalist, to the propagandist, to the lawyer, to the statesman - even, I think, to the prophet and to the soothsayer. ..."

....."...We have shown that the concourse of 44 nations are actually able to work together at a constructive task in amity and unbroken concord. Few believed it possible. If we can continue in a larger task as we have begun in this limited task, there is hope for the world. ..."

Can the international community today repeat that endeavour, rekindle that hope? One would need to invoke once more, as did Keynes, "a spirit of wisdom, patience and grave discretion". And any such attempt would feature a much greater number of effective protagonists rather than of mere participants. Sitting at the table for Europe there could no longer just be an undefeated and victorious Great Britain, with its great national and imperial traditions. Europe would be the only subject able to count for something - a United Europe through the institutions of the Union. But its role would only be recognized if it proved capable of abandoning the purely national approaches and reserves which have recently limited its contribution to adopting the instruments to be used in the current world financial crisis.

All I have said, the very thread of my remarks before this Institute, with all its vast experience and competence, lead me to answer my opening question affirmatively, but on one condition as I made clear as I went along.

Yes, Europe can live up to its responsibilities in a globalized world, but on condition that it recognizes itself in the Union born of the Community founded almost sixty years ago. On condition, that is, that we provide ourselves with stronger common institutions, stronger common policies and greater common budget resources.

I am well aware that this conclusion may contradict Great Britain' s traditional reluctance to fully accept the prospect of European integration and political unity. But let me remind you of the words which a great Englishman and great European spoke at the Albert Hall on May 14th 1947. I quote : "It is necessary that any policy this island may adopt towards Europe and in Europe should enjoy the full sympathy and approval of the peoples of the Dominions. But why should we suppose that they will not be with us in this cause? They feel with us that Britain is geographically and historically a part of Europe, and that they also have their inheritance in Europe. If Europe united is to be a living force, Britain will have to play her full part as a member of the European family".

I am confident that the old message from Winston Churchill, still sounding so inspired and farsighted, can be accepted and fully shared by the Nation that he led in the years when, under his guidance, Great Britain successfully defended itself and Europe, saving our freedom, our civilisation, which we will never forget.