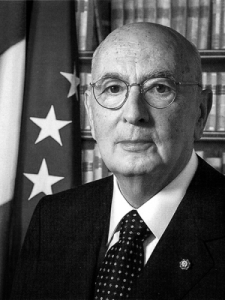

This is the text of the letter which Italian President Giorgio Napolitano sent Reset in reply - last October 29 - to editor Giancarlo Bosetti on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of Luigi Einaudi's death.

Dear Director,

Every day now we find ourselves confronted with the crisis of the European design which represented the greatest political invention of the second half of the XX Century and which generated so much dynamism and potential as to establish itself as a reference point and perhaps even as a model far beyond Europe's borders. And what finally emerged was the crisis of a political leadership that should have fostered at the start of the new century a coherent development of the process of European integration. We are faced with an historical failing which stands in sharp contrast to the "clearly superior class of statesmen" which once inspired and guided Western democracies. Quoting Tony Judt's assessment (he included Luigi Einaudi among those statesmen) you raised the still-open question of whether the entry of those personalities into the political arena and their rise to power was determined by historical circumstances or by the culture of the times.

Now if we look at Europe and Italy as they emerged from the tragedy of Nazism and fascism and the Second World War we can see clearly the ineluctable and crucial trials which then drove - in a context of new-found liberty and re-born democracy - old and new political groupings and men who were not only determined but also morally and socially sensitive to tackle their responsibilities and in so doing to make it possible for their countries and for Western Europe to accomplish an extraordinary leap forward. What proved decisive was not only the pressure of historical events but the cultural progress achieved in the years following the great depression and preceding the Second World War.

If that is how the European project was born and the process of community integration began, that process - after having progressed with ups and downs and overcome a number of crises - reached a turning point immediately after of the great changes of 1989. Once again the leverage exercized by "circumstances" and historical necessity was powerful but the fact remains that a political class stood ready to take up the challenge, a group of people who had been tempered by the community experience and from that experience had acquired both a breadth of vision and institutional expertise. The result was the Treaty of Maastricht and the decision to adopt a single currency.

We, especially in Europe, have now arrived at a third appointment with history: we now need to implant - at new depths - our integration process within the context of a critical phase of globalization. But it must be admitted that this time Europe's leaders appear to have great trouble in rising to the challenge, particularly in terms of the continuing crisis of the euro. They seem obviously unequal to the task for reasons including a general loss of culture and the impoverishment of democratic politics. These circumstances have conspired to provoke fatal withdrawals to petty-minded, anachronistic positions and national prejudices.

In responding to the threats involved it is important to recover the capital of political culture we hold because it represents a still insufficiently explored treasure. And above all we should do so country by country, starting with ourselves in Italy. Hence Reset's reflection, which I keenly appreciate, regarding the legacy of Luigi Einaudi and his teachings (cf Reset 127). We also held a conversation, Dear Director, to discuss the question. Allow me now to make a few brief considerations.

For reformist forces, the need to pursue a new equilibrium in the economic and social spheres is especially pressing today with, on the one hand the unavoidable pressure of competition in a world that has changed radically and on the other the values of justice and better general living standards - the latter now concretely enshrined in terms and rights and guarantees established with the creation of Welfare State systems in Italy and Europe. Well, in order to understand and meet the challenges of a globalized market economy and to do away with accumulated residues of corporatism and excessive social protection, which have both remained very significant in our country, the lesson taught us by Luigi Einaudi can serve as an important and stimulating theme for reflection. Naturally, one may well ask oneself why that particular school of liberal thought should have been ignored or opposed within the reformist movement and more specifically by the left wing close to organized labour when, between the end of the 1940s and the 1950s, a new democratic political dialectic emerged in the new Italian Republic. The terms of that dialectic were in fact to be marked profoundly by an ideological conflict largely stemming from an international situation that would soon turn into the Cold War.

Dogmatism and closed thinking had the upper hand over ideas rooted in liberal culture despite the fact that such ideas existed in the PCI. It became hard to distinguish the truths of Einaudi's brand of liberalism and more in general of the liberal ideal and political approach in all its various forms. I described that atmosphere and those disputes, when I recalled Norberto Bobbio in 2009 and his dialogue-duel with the PCI on the subject of liberty in the 1950s.

It would certainly be worth while to reconstruct more closely than has so far been done the debate in the Constituent Assembly and the contribution made by Einaudi on important issues of general interest that went beyond "economic relations" (Title III of the first part of the Charter) or even the crucial Article 81. The account left to us by Guido Carli in Cinquant'anni di vita italiana (Fifty Years of Life in Italy) is interesting and evocative. He considered that "the economic part of the Constitution was unbalanced, leaning towards the two dominant cultures, Marxism and Catholicism". But at the same time between 1946 and 1947, "De Gasperi and Einaudi, in the space of a few months, put together a sort of "Economic Constitution" which they removed to a safe spot, outside of the discussions in the Constituent Assembly". The strategy was "born in and managed between the Bank of Italy and the Government". It aimed at national economic stabilization anchored in a vision of a "minimal State" that was open to the international monetary system's institutions and rules.

Indeed, despite the fact that, to use Carli's expression, what united the Catholic and Marxist positions in the Constituent Assembly was the "non-recognition of the market", from the first few years of the Italian Republic the Government's programme included the demolition of economic self-sufficiency, trade liberalization and finally the decision that Italy should join in the process of European integration.

With the Treaty of Rome of 1957 and the birth of the Common Market, Italy recognized and accepted the fundamental tenets of the market economy, the principles of free circulation (of goods, persons, services and capital), and the rules governing competition. What are still today denounced as omissions or as downright impediments in the Republican Constitution's "economic relations" section were overcome in the melting pot of European construction and the development of community law. Gradually the left - first the Socialists and then the Communists - came to recognize themselves in the acceptance and edification of that construction.

However, the greatest gap remaining between Liberal and specifically Einaudi's positions on the one hand and the Marxist-inspired left (as well as the positions held in practice by Christian Democrat governments) regarded the role and limits of state intervention in the economy. In the Assembly's debate on what would become Article 41 of the Constitution, Einaudi used stinging irony to distance himself from any talk of "plans" and "programmes" and from doubtful expressions such as "social usefulness". He was at the same time eloquent and absolutely firm in raising the problem of monopolies and of the need to stop them from being created, or at any rate to ensure they were subject to controls. But beyond the debate in the Constituent Assembly he more generally worked to ensure that the Liberals were distinguished not only by an anti-protectionist line but also by the clear conviction (in that connection, see Paolo Silvestri's analysis in the chapter of his book on Einaudi devoted to "Liberalism and the libertarian tradition") that the state should "tread very cautiously when intervening in economic affairs", warning at the same time that such intervention could lead to corruption. He went so far as to declare, "liberalism is not an economic doctrine but a moral theory".

It is, however, doubtless that in Italy, already from the 1950s, the State intervened in the country's economy with increasingly less "prudence" and sense of proportion. Initially, and for some considerable time, it intervened directly in productive activities, frequently as a proprietor (albeit under the more flexible form of the state holding system). Then came a growing use of public funding, and increasingly frequent use of current-account public spending motivated by political-electoral demands and interests with the consequent accumulation of a terrifying stock of public debt.

Now that the great and irremissible achievement that was the creation of the euro is being strongly undermined by the sovereign debt crisis in a number of states, including Italy, we can no longer avoid engaging in a profound and careful reduction and selection of public spending as well as in a corresponding process of de-bureaucratization and reorganization of public institutions and of their modus operandi. Such an exercize cannot but affect the parasitic degeneration of "Italian-style Welfare" and re-establish the motivations, objectives and limits of social policies, i.e. reform them in accordance with the demands of an era of global competition, with its consequent challenges to Italy.

On the one hand then, account must more than ever be taken of the realities of the market and of the widely recognized role of private initiative and enterprise, which need freedom and the absence of any hindrances to competition. And on the other hand there is the need to promote other essential components of a liberal vision such as Einaudi's. That vision - as well set out by Francesco Forte in the conference organized on 13 May 2008 by the Bank of Italy - postulated the "reduction of inequalities at the points of departure and arrival" in tandem with the values of the free market and considered that for the two to converge was possible. Forte also ably pointed out the very modern sense of "the principle of liberty as responsibility" that emerged from Einaudi.

Recovering such approaches and intellectual contributions in order to review and adapt the policies and government programmes of the forces working for reform to the new overall context should seem neither an inappropriate nor an arduous task. If it is indeed the case that, as some maintain, the success of Einaudi's liberal researches is confirmed by the achievements of the various people trained at his school, including eminent liberal socialists and socialist liberals.

The "recovery" I mentioned should be part of this new effort at improving European and Italian politics both culturally and morally, the need of which - Dear Director - was the starting point of this letter of mine. We can now only reflect on Italy by looking at Europe. And in so doing we once again encounter Einaudi as a great precursor and supporter of that idea of a federal union of Europe which we are called on today to re-launch with Einaudi-like courage, by aiming to coherently overcome the dogma and limitations of national sovereignties.