It is with a full awareness of the honour granted to me and the commitment required of me that I have accepted the invitation to speak at the opening ceremony for the 2011-2012 academic year of the Collège d'Europe. This is an honour that I feel most keenly since I have long seen this institution as one of the brightest beacons for the development and shaping of the European consciousness as it continues to develop. I know how many European Civil Servants have learned their craft in Bruges in a spirit of rigorous professionalism and absolute independence, combined with a sense of the limits of and respect for the sphere of political decisions. These remain essential conditions for the authoritative voice and effectiveness that the European administrations must maintain and foster.

As is customary, the academic year starting today is dedicated to a universally renowned figure and a field of crucial and common interest. For 2011-2012, that figure is Marie Curie and that field of interest is what she represents for scientific research and the role of women. Allow me to mention in the same spirit an Italian name, that of the great scientist and Nobel Prize Winner, Rita Levi Montalcini, and her civic commitment and her support for the cause of women in Africa. A commitment that was recognised already some years ago with her appointment as a Senator for life by the President of the Republic.

I accepted the invitation to speak here today not just as an honour but, I repeat and underscore, as a significant and delicate commitment with respect to the times, or should I say this difficult historic period, which Europe, and for Europe the European Union, are experiencing.

For many months now the "Europe question" has on a daily basis dominated political communication, economic news, and the attention of citizens and households, in all of our countries. It is present and dominant in critical terms, in view of our steadily growing concerns with respect to the uncertainties of our daily lives and our common future and destiny. Equally, however, as perhaps never before, a perception has spread of what binds us, of what binds our societies and our people throughout a Europe that has, step by step, become united in an unprecedented process of democratic integration.

Hence the responsibility - that we all share - to grasp the opportunity thrust upon us by sudden, dramatic developments in the socio-economic context, a context that is not just European. A responsibility to explain ourselves to each other, to reflect on the past and on the present. We need first to cast some light on the progress made in the bold project announced on 9 May 1950. This is especially true nowadays since my generation is the last one to have lived through the tragedy that the Second World War unleashed on our countries, already battered by the First, Great War. Mine is the last generation to preserve a keen memory of the fatal divisions and destruction from which we had to raise ourselves up once again.

And now, after more than half a century of unity and constant progress, we need to reflect, in a clear and convincing relationship with our citizens, on the crisis that has swept the Eurozone. And we need to provide them with credible answers.

Essentially, we need to convey clearly to public opinion just what is at stake for our continent. And not just for our continent. Recent comments by non-Europeans on the risks that our difficulties could pose for the entire world economy somehow constitute an objective recognition of Europe's importance in today's world, even though the picture has radically changed as an effect of the headlong process of transformation and globalisation.

The reflection, looking to both the past and the future, that I urge you to make here today, does not disregard the imperatives of the present. Nor does it disregard the choices that Europe and its institutions are now called upon to make, almost - if you will - on a daily basis. I have the greatest respect for the effort being made by the Heads of State and government, the leaders of the European institutions, the policy- and decision-makers, in view of the dilemmas they have been facing since the serious crisis struck the Eurozone.

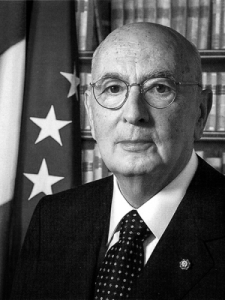

As I speak to you today I am no longer a member of their ranks. I am a Head of State without executive powers, but I know the effort involved in choosing and acting. Yet I feel that I share the responsibility, for good and for bad, for what Europe has experienced in recent decades. I feel the burden of that shared responsibility in view of the functions I covered in the past - in the Italian and European Parliaments, for a short time in the Italian Government and for a much longer time in the political and cultural movement in favour of European unity. I hope, therefore, that you will understand the spirit - neither recriminatory nor pedantic - of the critical considerations I will be making here today.

I will not dwell here on the run-up to the Eurozone crisis, that is, on the financial crisis triggered on a global scale by the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008. A crisis that had been brewing for a year-and-a-half and which had undoubted origins in, and therefore deeply penetrated, the real economy.

Opinions, which are hard to dispute, on the original and underlying causes of the global crisis are well known. The foreign debt of the world's most advanced economy; the growth, for many years - in the United States - in public and private spending that exceeded the income of either sector, with the effect of fuelling "growth without savings" ; and the consequent abnormal global imbalances.

What interests me is to underscore - and I will limit myself to this - a factor that has been indicated as one of the critical elements that over several decades has come to undermine the international economic system : the misleading assumption that the markets in general, and the financial markets in particular, are capable of self-regulation and therefore do not need public regulation .

It was precisely by observing the damage caused, and the danger created, by this assumption that governments in all continents came to understand the need to put in place a new system of rules that are capable of establishing effective global economic governance. This is the task that a newly created institution, the G20, has taken upon itself, and on which it continues to work, albeit not without difficulties and contradictions.

For Europe, the question presents itself in unique terms: that is, it is also an internal matter inherent to the development of the integration process we brought forwards so far, in which an operational system of common institutions and rules does exist, but needs to be reviewed and strengthened. It is around this acute need that the problematic and intense discussion aroused by the Greek crisis, by the Irish and Portuguese crises, but also by the tensions and risks that have hit Spain and Italy in terms of sovereign debt crisis, revolves. I intend the discussion which is being conducted in the European Union, the Eurozone and its various institutional expressions.

The European institutions and national governments have reacted, and continue to react, to these events with extraordinary measures and significant innovations. One example is the creation of three new supervisory authorities and, most notably, the creation of the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF). This will be succeeded in 2013 by a permanent mechanism that will pursue the same ends in a systematic and longer-term manner. The contribution that has been made by the European Central Bank - including, in some cases, by filling a political and institutional vacuum - is to be appreciated.

I cannot draw conclusions - not least because it is not within my remit to do so - on all the decisions and interventions whose progress has been marked by meetings of the European Council, together with the Eurogroup, for example on 21 July of this year and again in the past few days.

We also need to bear in mind the important legislative package on economic governance approved jointly by the Council, the Commission and the Parliament. My address here today simply includes a number of observations on uncertainties and disagreements that have marked the path followed by the Union in 2011 and which touch, revealingly, on underlying unresolved problems with respect to the common European project and its future.

The great question is what the decision to adopt the single currency - therefore, the birth of the euro - has represented. It is also, and in more general terms, what follow-up should have been, but was not, given to the Maastricht Treaty.

That Treaty represented an historic advancement - and it remains a milestone - in the European integration process. The decision to adopt a single currency was an integral part of that process, but one that cannot be separated out from its broader overall framework. The many years that led to Maastricht - and never before or since has there been a more careful, gradual, considered and debated preparation of a European treaty - and the final decisions reached with such effort, bear the mark of the far-sighted leadership of the member states of the time and above all of the three major founding countries.

For Italy, we can cite the government figures who led the six-month European Presidency in the second half of 1990 and played a significant part in defining the Treaty. I would like in particular to remember Guido Carli, as well as diplomats of great standing and civil servants of the calibre of Carlo Ciampi, Tommaso Padoa Schioppa, Mario Sarcinelli, and Mario Draghi. For Germany, more than any other we have Helmut Kohl, who understood with exceptional clarity and courage the need to link German unification, which had become an achievable aspiration, with a major advance on the path to the economic-monetary and political union of Europe. And for the European Commission, let us remember President Jacques Delors, author of the decisive Report of 1989.

In Maastricht, the fruit and the legacy of the three pre-existing Communities were harvested and the European Union was born. This was most certainly not just a change in the semantics. It was a political change, and a decisive expansion of horizons and goals. At the centre, most definitely, was the imminent prospect of the introduction of the single currency and the establishment of a European system of central banks and a European Central Bank.

The great integration project was first set out in May 1950 and launched in 1951-52 when the treaty founding the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) was signed and entered into force. With Maastricht it reached a level and a depth of historic note, by transferring monetary sovereignty - an attribute that, like the sword, like the army, was in every doctrine the preserve of the nation States - to the supra-national level. When today those of us who have institutional or governance roles in the Union say loudly that the euro is a vital pillar of the united Europe, we are referring first and foremost to the historic value of its introduction in the spirit of a federal Europe. Values that would have been, better than by anybody else, appraised by Altiero Spinelli, if he were still alive, crowning his prophetic endeavours.

To back this statement, it is only right to document and highlight the benefits that the existence of the euro has generated for all those countries who joined it, without exception. It is right and necessary to do so with greater conviction than we have done thus far, in the face of the turbulence experienced during this difficult 2011. We have on occasion been guilty of hesitating to react to waves of opinion founded on misinformation and the spread of petty national prejudices. But all of this is not enough. We need to draw attention to two other elements.

The first concerns the genesis of the single currency. This was conceived and adopted on the basis not of an abstract model, following a prejudicial vision of federalist inspiration, but of a real evolution of the European construction, in accordance with an internal, and by that time mature, need.

The experience of the European Monetary System (EMS) in the 1980s was revealing. The limits of the EMS emerged as progress was made towards the full implementation of the principles sanctioned by the European Community's founding treaty and the completion of the Single Market.

The problem set out by Tommaso Padoa Schioppa with the "irreconcilable quartet" formula was becoming unavoidable: free trade, free movement of capital, fixed exchange rates, and autonomous national monetary and macro-economic policies in a system of sovereign states cannot co-exist for any great length of time. The only way out was the transition - in a Europe already becoming increasingly integrated - to monetary union. This was an objective necessity, an awareness of which was gradually growing.

The second element to which I wish to draw your attention is the true content of the recent discussions, which have now been under way for months, and the further decisions to be taken at the European level. No substantive argument has been produced that puts in question the validity and irreversible nature of the decision to adopt the euro. In the early 1990s, when that decision was taken, there was no alternative to monetary union. And there is no alternative today to continuing along the path of the euro. The real issue is the relationship between monetary union and political union: an issue that those who helped prepare the Maastricht Treaty and the final negotiations were well aware of. But what was lacking then and, above all, afterwards?

The concept of political union has often been evoked in a somewhat indefinite manner. In general terms, the European integration process was undoubtedly political in origin and in substance. It is no mere chance that it initially sprang from the goal of Franco-German reconciliation as a condition for peace in the heart of Europe. In effect, in the course of its 40 years the Community has gained an international dimension. It has equipped itself with an instrument for foreign policy cooperation and played a role, by no means negligible, in the world of international relations. And, more generally, in its development the Community "construction" has acquired many other dimensions that do not simply serve the needs of the common market.

That said, with the transformation from Community to Union new political goals were set and found their place in the Maastricht Treaty. A common foreign and security policy, European citizenship, an increased role for the European Parliament. But the matter at issue, the substance of a process of political union, lay in a further, resolute expansion of shared sovereignty, to be exercised in common at the European level, an expansion with respect to the sovereignty of national states.

The bold and highly important step of transferring monetary sovereignty to the supra-national level had been taken. But was that enough? Or were the "accompanying" instruments envisaged in the Treaty adequate, with respect, in particular, to the rules governing the budgets of eurozone member states? Could an approach designed simply to coordinate national economic policies, like those with which the ambitious Lisbon Strategy - years after Maastricht - was entrusted, thus condemning it to failure, be enough?

When the British Chancellor of the Exchequer responded to the Delors Committee Report in April 1989 that "monetary union would in effect require political union and that is simply not on the agenda", he undoubtedly grasped the crucial point. At that time, a number of convinced and sincere pro-Europeans would also have preferred to suspend the decision on the single currency in order to anchor it to the birth - whether close or remote - of a European Federation. But, given that the time was ripe for the transfer to monetary union, this was an unrealistic position.

What could, rather, be postulated was the contemporaneous transition to a monetary policy, a fiscal and budgetary policy, and a macro-economic policy firmly entrusted to shared European sovereignty. And this is the political knot that now needs to be untied.

Only by advancing in this direction can the principles, values and goals that are close to all of our hearts be guaranteed. These are: financial stability, shared responsibility and solidarity, and the competitive growth of the European economy as a whole, according to the vision which one year ago Chancellor Merkel called here for in impassioned tones as the proper model for a united Europe. "A model for society and a way of life", she said, "that combine the strength of competitiveness with social responsibility". And I need hardly remind you in this respect of the importance of the European Social Charter whose 50th anniversary we are celebrating.

But has the time not come to recognize that faced with the Greek and Eurozone crises some countries manifested in the past few months hesitation and resistance, giving a sensation that the principle of solidarity has been obscured? Has the time not come to overcome what has seemed like a taboo with respect to the various suggestions for the introduction of European bonds? To overcome persistent reservations with respect to the adoption of effective rules and means to pursue a common development strategy? I refer to the strategy which the Commission has proposed for 2020 but whose binding, effective implementation still needs to be ensured?

And how can we fail to see the insurmountable contradiction between the need for a major advance in the integration process and in the assertiveness and productive capacity of a united Europe, and, on the other side, a restrictive approach to the task of the Union's financial prospects for the period from 2014 to 2020? Each and every one of us must ponder these questions.

To put it bluntly : each eurozone member state must play its part, must fully assume its responsibilities. And these most certainly include Italy: a culture of financial stability has had authoritative and coherent supporters in our country in the exercise of their public functions but for many years now that culture has not prevailed.

Now, we can no longer vacillate in the face of the categorical imperative of a substantial and constant effort to lower our public debt. Nor can we waver in the face of the structural reforms that will pave the way for new, more intensive economic and social growth. These are undoubtedly hard tests, but we need to tackle them. In recent months we have begun to do so, but a lot still needs to be done, without delay. No Italian political force can continue to govern, or present its candidacy to govern, without showing that it is aware of the decisions, albeit unpopular ones, that need to be adopted in the interest of the Nation and in the interest of Europe. Guido Carli, governor of the Bank of Italy from 1960 to 1975, wrote shortly after the signing of Maastricht: "the Italian political class has not realised that, by approving the Treaty, it has already accepted a change of such magnitude that it is unlikely to emerge unscathed". His words still hold true today.

Each of us must play its own part, but together we must respond to the questions - both current and future - that I mentioned earlier. Since the birth and first steps of the European integration project, the understanding between France and Germany has played an essential role. We need only recall, once again, the names of Schuman and Adenauer, and with them the great figure of Alcide De Gasperi. As Italians, we can boast of a long history of constant, decisive support for the European project, and we continue today to respect the irreplaceable input of France and Germany - our two great European friends - and of their leaders.

We particularly respect, as we always have, Germany's dedication to the European cause, and we admire the successes it has achieved, acting as a great democratic country, at the economic and social level and in the field of monetary stability. We understand, too, the historic reasons for Germany's attachment to this essential pillar. It is in a spirit of friendship that we express our concern for an apparent reluctance to accept further, and by now inevitable, transfers of sovereignty - and therefore also of majority decisions - to the European level. After all, both the German Chancellor and the French President have recently put forward proposals that were subsequently translated, in part, into the Euro Plus Pact. These have the potential to break down the rigid dividing wall that was requested in the current Treaty to protect individual states' competencies from a progressive extension of those of the Union.

The leaders of all our countries must come to share a common awareness that it is mandatory to leave behind us that kind of limits which remained not just in the aborted Constitutional Treaty but also, and even more so, in the Lisbon Treaty that followed it.

The need for "more Europe" has been expressed unequivocally in the succession of appeals, some of them accompanied by a wealth of concrete recommendations, presented by experienced and authoritative European figures. It has become categoric evermore clearly in a world, shaken as it is by the crisis we are currently experiencing, in which no individual European country, not even the biggest and most efficient one, can "save itself by itself" or play a significant role using its own forces alone.

That call for "more Europe", in contrast to an undeniable tendency for nations to look inwards rather than outwards, if not to think nationalistically, requires the exercise of greater decision-making powers by the institutions of the Union. Such powers should be exercised in a climate of mutual respect and renewed collective acting, beyond proposals by individual governments during the formulation of guidelines and decisions.

For the Council, collective action hinges on the guarantee provided by the "permanent" President established by the Lisbon Treaty. For the Commission, it again revolves around the role of the President. The latter would, however, most certainly be favoured by a reform - envisaged for the years following 2014 - through which new criteria would be adopted for a more restricted composition of the Commission, independent of national influence.

The Community method - which sees the European Parliament too play a leading role, on an equal footing - remains incompatible with any inter-governmental drift. It does, however, provide adequate space for the "coordinated action by member states" stressed by the German Chancellor. The key point is not to undermine the functions of the more properly supra-national institutions, Commission and Parliament.

We must in any case avoid fuelling a misleading argument on the spectre of a terrible European "Super-State", a new Leviathan. The outcome we should be working towards is not a replica of European nations' historical model of what is, to a greater or lesser degree, a centralised and heavily bureaucratic state. Rather, we should be striving for a more complex and variegated multi-level construction, regulated by a flexible principle of subsidiarity.

We should, however, be asking ourselves whether a more consistent sharing of sovereignty and decision-making powers at Union level now requires a new Treaty. The question is not without foundation and cannot simply be put aside.

My own personal experience of seeing the Constitutional Treaty, in spite of corrections by the IGC, "buried by referendum", as well as the memory of the long, enervating ratification period to which the Lisbon Treaty was subjected, impels me to suggest that we give the question our most careful and cautious attention.

We need to carefully limit those elements of the Treaty that need to be reviewed and, above all, trying to overcome the unanimity constraint in the ratification process. There is even a risk that, by starting work on a new Treaty, we could create a vacuum or enter into a state of delayed action. On the contrary, we can and must work first and foremost, and immediately, to grasp the opportunities in the existing Treaty, not least to strengthen the budgetary rules and the supervision of economic policy trends in the eurozone.

In conclusion: let us concentrate on what needs to be done right now. At the same time, however, let us try to enlarge our vision in order to present the European debate to the younger generations in a new and fresh light.

We will not let the euro fall to speculative attacks and waves of panic in the financial markets: no-one should be in any doubt on that score. And no-one should think that they are watching the entire European construction totter. Over the last 10 years it has equipped itself, through the euro, with a new, essential pillar and source of strength. But in the much longer span of 60 years it has defined and consolidated itself as something much bigger, bigger by far than its purely economic and, more recently, monetary dimension.

A continent rich in traditions and resources has gradually become united - in all its diversity -, thus giving rise to an integration process that has become a beacon for the entire world. A community of values has been forged, and with it a complex and variegated community based on the rule of law and inspired by freedom and democracy. And this has given rise to the masterly elaboration - such an extraordinary unicum! - of a body of community law, the development of and respect for which is overseen and guaranteed by a system of supreme courts.

From the creation of a space of freedom, security and justice to the introduction of a Charter of fundamental rights, the Union has seen a continuous expansion of its horizons. At the same time, the prospect has taken shape of a common vision and capacity for European action in the field of international relations, defence and security.

I do not underestimate all that is unsatisfactory in Europe's balance sheet.

I wish to say, however, that the European construction now has such deep foundations that the permeation of and the interconnection between our societies, our institutions, our societies, and the citizens and governments of our countries, is so deeply rooted that nothing can cause us to turn back. Any break-up of this construction is unthinkable. Anyone who imagines the contrary should desist from such wishful thinking.

But we men and women from all parts of Europe must regain our awareness of and pride in the integration project and process that has united us. Let me say, to young people in particular: your future is here, not somewhere "else", and far less in any trend for our countries to look inwards or in an impossible return to the past.

Everything has changed with respect to the starting point, that far-off 1950, but we are supported by strong new motivations. We have endowed our Union of states and peoples with increasing strength. The mission of that Union is to preserve - within a disorderly and unregulated globalisation that could otherwise swallow us up - our identity, our model of integration and unity, our insuppressibly unique input to the historic development and future of world civilisation.

It is this mission that must inspire us. Especially now that we can see and touch at first hand the inequalities, imbalances and injustices that are and continue to be released by the pressures exerted by irresponsible oligarchies and by the exaggerated weight of finance that we have witnessed in recent times. An even more integrated and assertive Europe is the only possible framework of reference within which we can work to clear a pathway of sustainable development in our countries, to avert the danger that looms over our young people.

The danger I refer to is that of a serious recession, a future where an entire new generation is robbed of the prospect of employment and social affirmation.

So I say to our young people: set your sights on Europe, and especially on that social commitment that has always been an inherent and distinctive element of the European vision of economic development. Today more than ever, that commitment needs to be revitalised. I remember a proposal that was made - sadly, unsuccessfully - during the discussions leading up to Maastricht and the decision to adopt the single currency. That proposal was the one of the convergence criteria for euro membership would be a limited unemployment rate, especially youth unemployment. This is an example of the social ethos that we must recover, strengthen and bring up to date.

If we are to resume the old and new reasons underpinning the European project to public opinion, to citizens and to young people, an element which thus far has been lacking in terms of democratic legitimisation and validity is required. That element is a transparent public debate, a political discussion reaching across national borders and potentially leading to the direct election of the president of the Union's governance body. The growth, at last, of structured political and social actors at the European level, a parliamentary dimension in which representation in the European Parliament - which has achieved so high and incisive a role - is integrated with representation in national Parliaments, in a network of institutional relationships that involves regional and local authorities as fully as possible.

Is this not, perhaps, a programme that can stimulate and mobilise the younger generations and rekindle their interest and faith in politics?

Those who, in looking to the future, believe in the European project as an essential and inevitable choice, must become more demanding in their commitment. In October 1989, at another crucial moment in our history, speaking here for the opening of the Academic Year, Jacques Delors said: "I have always been a believer in politics by small steps, but today I take distance from that approach because our time is limited. A quality leap is required both in our concept of the European Community and in our external action".

In those years, with the Maastricht Treaty and the euro, that such a leap forward did indeed take place. It is now time to make another, and even more decisive, one.